Baseball historians normally don’t point to October 1, 1967 as a consequential date in Major League Baseball history but in retrospect that date was a turning point.

It was the day the Kansas City Athletics, or A’s, played the franchise’s final game in Kansas City. For the most part, the Kansas City A’s franchise is relegated to the dust bin of baseball history, since the team played just 13 years in the Missouri city.

But that franchise’s owner—Charles O. Finley— and his team changed baseball.

In 1960, the Kansas City A’s were purchased by Finley, a Chicago insurance broker, from Arnold Johnson, who originally got the team from Connie Mack on November 5, 1954 and moved the A’s from Philadelphia to Kansas City in time for the 1955 season.

Finley stepped in as the Kansas City A’s owner and changed the way baseball marketed its product in numerous ways. Baseball uniforms became colorful. He threw gadgets into the park like a mechanical rabbit that popped out of the ground behind home plate when the umpire needed new baseballs. He had a home run porch in the outfield in Kansas City. He proposed that players should all be free agents after every season.

Most of Finley’s ideas were considered at best goofy and at worst as anti-baseball.

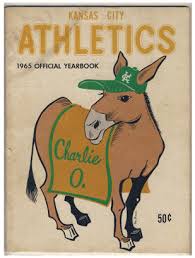

For example, he dumped the Athletics’ elephant logo and replaced it with a mule that traveled with the team.

“We had some episodes,” recalled Howard (Doc) Edwards who was a Kansas City catcher in the 1960s. “Once we came into New York City and we were staying at the Americana, and the Americana at that time was the elite place in the city of New York. They rolled out the red carpet but forgot there was a marble floor underneath it and the mule looked like Bambi on ice coming through the locker room. We had a lot of laughs because of the mule, but I really respected the animal because it was beautiful.

“It was a logo for Charley. It was like the team mascot. I think Charley, as it was proven later, was a promotional genius because of the different colored uniforms,” Edwards added. “…at the time a lot of people laughed at Charley Finley, but years proved he had a great mind and I think one of the things with the mule was the mascot and we’d get publicity for the ballclub.”

Finley had a zoo in the outfield and had sheep grazing, rabbits running around and, of course, the mule. Edwards contended the animals were not a distraction to the players.

“I think, before the game there was a lot of hoopla and publicity but once the game started the only time you would think of it was if someone hit a home run,” he said. “That bell or horn from the Queen Mary went off and the sheep started running across the hill, then you had to notice them, but otherwise once the game started you really didn’t pay any attention to it.”

Finley had wanted out of Kansas City and threatened to move his team to a cow pasture in Louisville, Ky., in 1964. Finley would finally leave for Oakland after the 1967 season, three years after the owners of the Milwaukee Braves decided Atlanta would give them a better business opportunity.

In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review a Wisconsin Supreme Court decision that found the Braves had not violated Wisconsin anti-trust laws, allowing the organization to move to Atlanta.

Because Finley’s wanted to move his team, too, influential Missouri Sen. Stuart Symington threatened legislation to revoke baseball’s antitrust exemptions. His ranting led baseball to announce plans to expand in 1968.

The American and National League’s acted separately with the American League moving back into Kansas City and Seattle. The National League would end up with Montreal and San Diego.

Finley’s move had prompted a series of actions. The American League met on October 18, 1967 to consider Finley’s request to transfer to Oakland and entertain expansion. The league on a second vote that day gave Finley permission to go immediately and approved a Kansas City expansion team to start play by 1971.

While Kansas City Mayor Ilus Davis and Sen. Symington weren’t opposed to Finley leaving immediately, they were against Kansas City being without a team for three years. Symington applied heavy pressure on the American League.

By midnight, American League President Joe Cronin opened the meeting again and announced plans to push expansion up by two years, meaning Kansas City would play ball in 1969.

It was one of the biggest change in baseball since the turn of the 19th century in 1968. Further, the American and National League split into divisional play and added a layer of playoff games because of the team moves and subsequent expansion.

In all, Finley’s move to Oakland resulted in six expansion teams in professional baseball.

For the record, Finley’s Kansas City A’s played the New York Yankees in its final game and lost, 4-3. It would be the 99th time in 161 games Kansas City suffered defeat.

In 13 years in Kansas City, the Athletics franchise never finished higher than sixth when the American League had eight teams (1955-60) and once finished seventh in the 10-team league. The A’s finished last five times.

Finley’s Oakland A’s would enjoy success, winning three straight World Series championships in 1972, 1973 and 1974.

Not too many people give the Kansas City A’s credit for changing baseball history. But it is a fact, the A’s relocation from Kansas City to Oakland changed baseball entirely.

Evan Weiner, the United States Sports Academy’s 2010 Ronald Reagan Media Award winner, can be reached at evanjweiner@gmail.com. He has written several e-books on sports, including, “The Business and Politics of Sports, Second Edition,” which is available at www.bickley.com and Amazon.com.