It all sounds very familiar. Warnings about the lack of progress from the International Olympic Committee (IOC), disputes over venues, delays in construction, strikes by workers, health concerns and even a team of refugees. But this is not a tale from Rio 2016 but 60 years ago.

Melbourne was preparing to become the first city from the southern hemisphere to stage the Games. This week in 1956, athletes from some 72 nations were gathering in the city.

In fact, Melbourne had won the Games by one vote from a South American city, Buenos Aires. These Olympics had been over a decade in the making. The Victorian Olympic Council had decided to table a bid in 1946, barely a year after the end of the war. The bid book was lavish, bound in suede. There was even an extra special version with a lambs wool cover.

The Prime Minister Ben Chifley told IOC members that his Government “cordially supports Melbourne’s plans for the holding of the Olympic Games in 1956” for what he described as “this historic event in the south-west Pacific.”

The decision was made in Rome in 1949. Melbourne sent a delegation of four, led by Lord Mayor James Disney. Curiously, Australian IOC member Hugh Weir was not present at such an important meeting, unable to attend because of business commitments.

The victory celebrations that night were marred by the activities of a smartly dressed confidence trickster who relieved many IOC members of the contents of their wallets. It was not an auspicious start.

When EJ Billy Holt, a chief organizer of the 1948 London Games, arrived to take up a planning role with the Melbourne Games, he found an organization locked in a bitter dispute about the site of the main stadium. No fewer than seven options were proposed including the Royal Showgrounds, Melbourne University and the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG).

Organizing chief Wilfrid Kent Hughes was drawn into the arguments. He was a supporter of using the MCG and talked bitterly of obstruction from “the arch priests of cricket.” In time it would need mediation from the likes of Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies to find a solution.

Further squabbles about the financing of the Games, and the selection of other venues, presented a very negative picture.

Australian Athletics official Arthur Hodson warned: “There is no doubt what the International Olympic Committee will do about the 1956 Games if Melbourne cannot give a suitable guarantee.”

In 1952, the outspoken and dogmatic American Avery Brundage took over as IOC President.

He told Weir: “If there is the slightest doubt in your mind that the 1956 Games will be staged properly so they will be a credit to Australia and the Olympic Movement, give them up now and let us select another venue before it is too late.”

Melbourne seemed to be lurching from one crisis to another and in 1953 it became clear that their health legislation presented a very real problem. Quarantine laws would prevent the importation of horses for the equestrian competitions.

“Certain proposals have been submitted to the health authorities, with a view to special quarantine arrangements, under which it will be possible to bring horses into Australia, for the equestrian events,” organizers claimed. “These proposals are at present being examined, and we are hopeful that suitable arrangements will be evolved.”

It proved a vain hope. IOC Chancellor Otto Mayer called it “another black mark against Australia” and others echoed his irritation.

But the Australians found an ally in the British peer Lord Burghley, who suggested “begging our Australian friends to forgo the project of organizing the equestrian events.”

Five cities, including Rio de Janeiro, entered the race to welcome the horses but in the end the IOC chose Swedish capital Stockholm. It was the only time that a single Olympic sport had been staged on a separate continent.

Former IOC President Sigfrid Edstrom had suggested that the Games would be held in October. The start date was eventually fixed for November 22, the latest in the year it had ever been.

United States Olympic Committee secretary Asa Bushnell suggested that this was “obviously going to be pretty tough for all the College people who want to go.”

The organizers were now threatened with industrial action too. A carpenters’ strike slowed work at the MCG. Brundage was still unhappy with progress and flew to the city in 1955. He did not mince his words.

“Melbourne has a deplorable record [breaking] promises upon promises in its preparations for the Games,” he said. “For years we have had nothing but squabbling, changes of management and bickering.”

Then, most damning of all, he said: “More than ever the world thinks we made a mistake in giving the Games to Melbourne.”

By this time, it was all but impossible for the Games to be switched with little more than a year to go. Kent Hughes was furious and wrote to IOC vice president Lord Burghley claiming that the adverse publicity had cost the Organizing Committee anything up to $247,000.

“He made the job of the Organizing Committee ten times harder,” he said.

Brundage seemed to have been rather pleased with his bombshell. He told his fellow IOC members that: “My observations caused a grenade of sensation in the world’s press and had the effect of an atom bomb. I am sorry I didn’t say it earlier.”

Even the lighting of the flame in Greece needed a little help. Sunlight was lacking on the day of the Ceremony and organizers were forced to use a back-up flame.

When the flame finally reached Australia, it landed first in Darwin and then headed down to Cairns. It was carried first by Con Verevis, an Australian of Greek heritage, and then by aboriginal Anthony Mark from the Mitchell River.

As the flame traveled south towards the Olympic city, the runners encountered extreme heat and the route was also altered because of flooding.

By the time it reached Melbourne, the city was festooned in decorations to welcome the Games.

Many of the competitors had also arrived at the Village in the suburb of Heidelberg. The cost per athlete per day was set at £3 and 10 shillings.

These days dining facilities are open continuously but in 1956, although they employed 15 cooks who worked shifts, it was originally planned that they would close at 9 p.m. for reasons of cost. Organizers had little budget for landscaping the surroundings either. Plus ça change.

Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, dressed in full naval uniform, opened the Games on behalf of The Queen. As one Australian newspaper observed: “The Duke comes 15,000 miles by air and sea to say 16 words.”

The gates at the MCG opened four-and-a-half hours before the Opening Ceremony was to begin. In those days all ceremonies were held in daylight.

The Ceremony was very formal with military marches performed by the bands of the Royal Australian Air Force as the teams marched in. The host nation Australia were the last to enter the stadium. In their ranks was hockey player Brian Booth, destined later to captain his country at cricket. He was from New South Wales and observed later that “it was the first time I had ever been cheered by a crowd in Melbourne.”

The choice of oath taker was the popular middle distance runner John Landy.

The final runner in the Olympic Torch Relay was teenager Ron Clarke, who entered the stadium carrying a flaming Torch. To make it show up better in daylight, strips of magnesium had been added to the mix.

Clarke lit the cauldron and then discovered that his t-shirt had been singed by the sparks.

The scoreboard at the MCG was specially adapted for the Games. Ordinarily it carried the scores for cricket and Australian rules football. On the upper section above the results there was a message from Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the Frenchman who had revived the modern Olympics.

“The Olympic Movement tends to bring together in a radiant union, all the qualities which guide mankind to perfection,” it read.

That “radiant union” was sadly lacking in world affairs. This was one thing that was beyond the control of the organizers. The official report talked of the “atmosphere of menace.”

A crisis in Suez escalated into military action involving Great Britain and France. Egypt, Lebanon and Iraq pulled out of the Games. In Europe, The Netherlands also withdrew even though some of their team had already reached Melbourne.

Spain were another who decided not to take part, but future IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch symbolically raised the Olympic flag above the Barcelona Olympic Stadium in a gesture of solidarity which was not forgotten.

As the IOC met in Session before the Games, Brundage told his members: “We hope those who have withdrawn from the Melbourne Games will reconsider. In an imperfect world, if participation in sport is to be stopped every time politicians violate the laws of humanity, there will never be any international contests. Is it not better to try and expand the sportsmanship of the athletic field into other areas?”

A resolution, composed by the Frenchman Jean de Beaumont for the IOC, told those who stayed away that they considered the abstentions “contrary to Olympic ideals” but their appeal had little effect.

In 1956, the refugees came not from the Middle East but from Hungary. An uprising had been viciously repressed by Soviet tanks and members of the team escaped through Czechoslovakia to Switzerland. From there they flew to Australia. When they arrived they received a wildly enthusiastic welcome. Many waved flags bearing the pre-communist Kossuth coat of arms and their struggle was highlighted by one memorable episode.

There have no doubt been water polo matches every bit as violent since, but the clash between the Hungarians and the Soviets in the Olympic pool became emblematic.

When a blood spattered Hungarian player, Ervin Sador, climbed out of the pool after a clash with a Soviet it sparked an angry reaction from the crowd and police were called to restore order. The Hungarians were awarded the match and went on to take the gold medal. Less well remembered were crowd demonstrations during the team saber competitions, when Hungarians fenced against the Soviets.

When the Games were over, many Hungarians did not return to their homeland.

It was not without irony that one of the stars of the Games proved to be a competitor wearing a red Soviet vest. Vladimir Kuts was Ukrainian. He had joined the Soviet navy where his talent for running came to the notice of coaches. He set Olympic records as he completed the 5,000 meter and 10,000 meter double.

The Games proved golden for the host nation who in addition to their sports training, received “drill instruction” from the Australian Army.

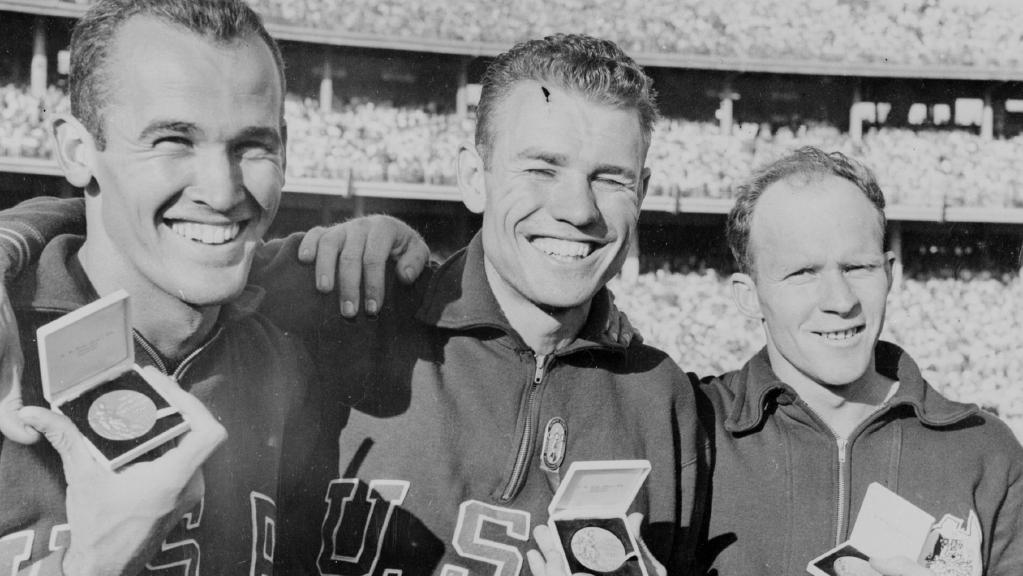

Swimmer Dawn Fraser forged the first chapter of a legendary career in the pool, though she sportingly admitted it might not have been so easy had the Dutch swimmers not been forced to withdraw. On the track, Betty Cuthbert starred with three gold medals and Shirley Strickland retained her hurdles title then raced over 80m. No Australian men won gold on the track but future IOC vice president Kevan Gosper was part of the 4x400m quartet which came home with silver.

Australian Rules football made an appearance as a demonstration sport. A team representing the Victorian Amateur Football Association beat a Combined Victorian Football League and Victorian Football Association team.

“The game was played in the true amateur spirit with abundance of vigor and speed,” said organizers, who noted that the spectator participation or what they described as “outspoken barracking” was missing.

It was football, as it was played in the rest of the world, that provided the last gold medal to be decided.

The tournament had not been without problems. Some countries withdrew because of the cost, others because it coincided with their domestic club football. Legendary goalkeeper Lev Yashin won Olympic gold with the Soviet team. The final against Yugoslavia was played shortly before the Closing Ceremony.

In contrast to previous Games, many of the competitors decided to stay on in the Melbourne sunshine. This made it possible for a change to the Closing Ceremony that has endured to this day.

A letter from an anonymous “Chinese boy” had landed on the desk of organizing chief Kent Hughes suggesting an unusual parade of the competitors

“War politics and nationality will all be forgotten,” he wrote. “During the march there will only be one nation. What more could anybody want, if the whole world could be made as one nation?”

Long after the Games, the writer was identified as carpentry apprentice John Ian Wing. He had followed the Games on the radio at home and had not seen a single event live. The organizers acted with commendable speed and the march took place as Wing had suggested. It made an immediate impression with some very influential citizens.

“They went around the arena as men and women who had learned to be friends, who had broken down some of the barriers of language, of strangeness, of private prejudices,” said Menzies.

“In the minds of many thousands who saw the Melbourne Games there still lives a green and pleasant memory.”

Organizers set the cost of these Melbourne Games at some $9.8 million. Even allowing for inflation it seemed a remarkable bargain.

By Philip Barker

Republished with permission from insidethegames.biz.