By Philip Barker |

The Court of Arbitration for Sport has announced the Russian appeal against the sanctions imposed by the World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) will begin on November 2. If this hearing goes ahead it will go a long way to establishing who can take part if the Olympics open as planned on July 23 2021.

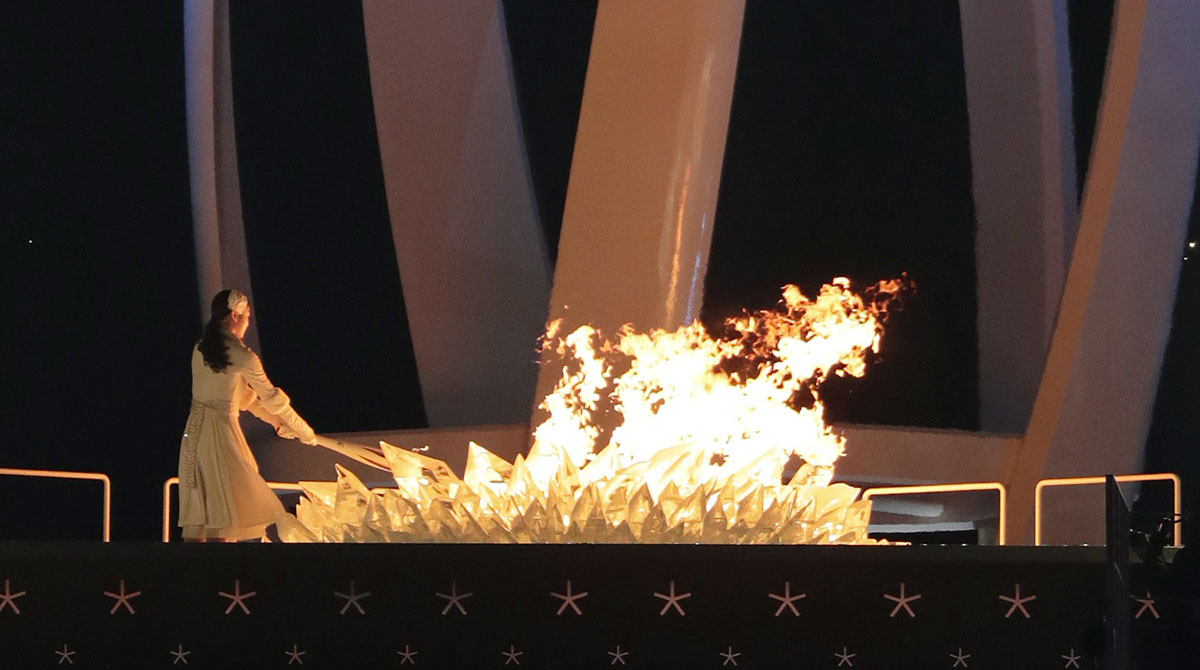

Apart from the legal approach, the Olympic Movement also has a long-standing symbolic act which the International Olympic Committee (IOC) insists “is fundamental to the correct communication of the Olympic values and ideals. One of the key elements of the Opening Ceremony is the three oaths taken by athletes, followed by officials and then the coaches.”

It was 100 years ago that the Olympic Oath was first introduced.

Belgian fencer Victor Boin spoke it in French at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics. His words translate as: “In the name of all competitors, we swear that we shall take part in these Olympic Games in loyal competition respecting and abiding by the rules that govern them, and desirous of participating in them in true spirit of sportsmanship for the glory of sport and the honour of our nations.”

Nowadays, the majority of disqualifications are for doping. There were some offences in the early years. 1904 marathon winner Thomas Hicks was said to have been given strychnine.

In that same race another American runner, Fred Lorz, wrote his name into the records for cheating in an unusual way.

“Spectators were gathered at different points along the way and lustily cheered the racers as they passed. A vanguard of horsemen cleared the thoroughfares and judges, physicians and newspapermen followed in automobiles”, said the New York Times.

At the halfway point, Lorz, a member of the Mohawk Athletic Club, stopped running and hitched a ride.

Later, suitably restored, he resumed the race with just under 10,000 metres to go. He crossed the line first but “was immediately disqualified on the charge that he had ridden about three miles in an automobile in traversing the course over the country roads.” Lorz admitted he had suffered “physical exhaustion for a time.”

At first he was banned for life but was later allowed to compete again.

At the time, most sports did not have an International Federation. Judges and referees were supplied by the host nation. At the 1908 London Olympics, there were bitter complaints about judging.

IOC President Pierre de Coubertin had already called for an oath which would “reintroduce a spirit of joy, honesty and selflessness into modern sport. It will renovate them and make collective muscular exercise a true school of moral improvement.”

He based his idea on the ancient Olympics, where fines had been imposed for infringements. These were used to erect “Zanes” – statues of the gods.

In 1912, American Jim Thorpe won pentathlon and decathlon gold at the Stockholm Olympics. The Swedish King declared him “the greatest athlete in the world.” Soon though, Thorpe was stripped of his medals after Olympic officials discovered that he had received payment for playing little league baseball.

It prompted Coubertin to insist “a revision of the regulations governing amateurism was essential.” He considered the case of Thorpe.

“How can one think that for an instant, that if he had been called upon to swear upon his country’s flag, he would have run the risk of swearing a false oath?”

When the oath was introduced, the New York Times described it as a “typically French idea.”

In 1920, the behaviour of the Czechoslovakian football team suggested they had not taken it to heart. They were angered by the officiating of British referee John Lewis. After half an hour of the gold-medal match against Belgium, they were 2-0 down and then had a man sent off. At this point they walked off and lodged a protest, complaining “most of the decisions were incorrect.”

Their Belgian opponents were awarded the gold medal by default.

The Czechoslovakians were not the last to take issue with Olympic officialdom.

In the 1968 football final, Bulgaria had three men sent off and went down 4-1 to Hungary, who also had a man dismissed. All this came only a few days after FIFA President Sir Stanley Rous announced the launch of a diploma for the “most sportsmanlike team.”

By the Munich 1972 Games an oath for judges and referees had been introduced, but this did not prevent two infamous incidents.

In the hockey final, West Germany’s Michael Krause scored the only goal of the match. His Pakistani opponents, already unhappy with the officiating, demanded that the goal be disallowed. Some even attacked the judges table. At the medal ceremony which followed, the Pakistan players refused to face the German flag and showed little regard for the ceremony. A life ban was imposed although this was later revoked.

That night, the men’s basketball final was also fiercely contested.

The Americans celebrated victory over the Soviet Union before an official indicated that a timeout had been called, leaving three seconds still to play. When the match was eventually resumed, Aleksandr Belov scored a further basket to give the Soviets victory by one point. Protests were immediately lodged. US players’ representative Ken Davis made it clear they had voted unanimously not to accept a silver medal if the appeal was turned down. They refused to attend the medal ceremony and to this day their silver medals have never been collected.

In 1976, the flashpoint came in modern pentathlon, a sport devised by Coubertin himself. In those days competition was over five days. In fencing, Boris Onishchenko, a soldier in the Red Army, lined up against Great Britain’s Jim Fox.

As they fought, a light came on prematurely to indicate a hit for Onishchenko. Fox later recalled: “All I could think about was that Onishchenko had a weapon that was not properly working, and then over a period of minutes, because he was going to put it back in his bag and because of the way he he wanted to put it back in his bag, I felt there was something dramatically wrong.”

The judges took away Onishchenko’s sword for examination. Then came the bombshell as official Carl Schwende announced: “The weapon had definitely been tampered with. Someone had wired it in such a way that it would score a winning hit without making contact.” Onishchenko was sent home in disgrace and Poland’s Janusz Peciak went on to take individual gold.

“I always say that Scotland Yard is the best in the world for investigation, but Jimmy Fox really helped me to win the medal, because if Jimmy had not caught him, Onishchenko would have got away with this and would have won the gold medal instead of me.”

Cheating to win is one thing, but in 2012, eight players were disqualified from the badminton tournament at London 2012 for deliberately trying to lose matches. The players from China, South Korea and Indonesia had made basic errors in an attempt to lose some pool matches in order to achieve more a advantageous draw for the knockout stages of the competition. They were charged under the Badminton World Federation’s code for “not using best efforts to win a match.”

Yu Yang, one of those disqualified, later said: “We’ve already qualified and we wanted to have more energy for the knockout rounds.”

Although then-IOC President Jacques Rogge identified “match manipulation” as a growing threat, doping still accounted for most headline offences.

When Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson was stripped of his 100m gold medal at the 1988 Seoul Olympics after failing a drugs test, it was the biggest story of those Games.

The dopers became ever more sophisticated. Eventually in the wake of the Salt Lake City bribery scandal, the IOC set up the 2000 Commission. From the deliberations of their working groups came the establishment of the WADA.

In line with the IOC’s “correct communication of the Olympic values and ideals”, recommendation 34 was that “the athletes oath must include a statement concerning drug free sport.”

In 2000, Australian hockey player Rechelle Hawkes became the first to speak an oath “committing ourselves to a sport without doping and without drugs.”

By 2012, an oath for coaches had been included in the ritual.

At the 2018 Winter Olympics came a further change. In the words of the IOC, “these three oaths will be merged into one, considerably shortening this segment of the Ceremony, and athletes will recite the oath on behalf of the three groups.”

For most, oath-taking is a significant undertaking which sets participation in the Olympic Games apart. Yet bulletins detailing the changes to results after retesting are regularly circulated by the IOC. The sinister machinations which took place in the laboratories following Sochi 2014 further suggest that there are still some who are prepared to disregard the Olympic Oath in order to win at all costs.

Republished with permission from insidethegames.biz.