By Nancy Armour |

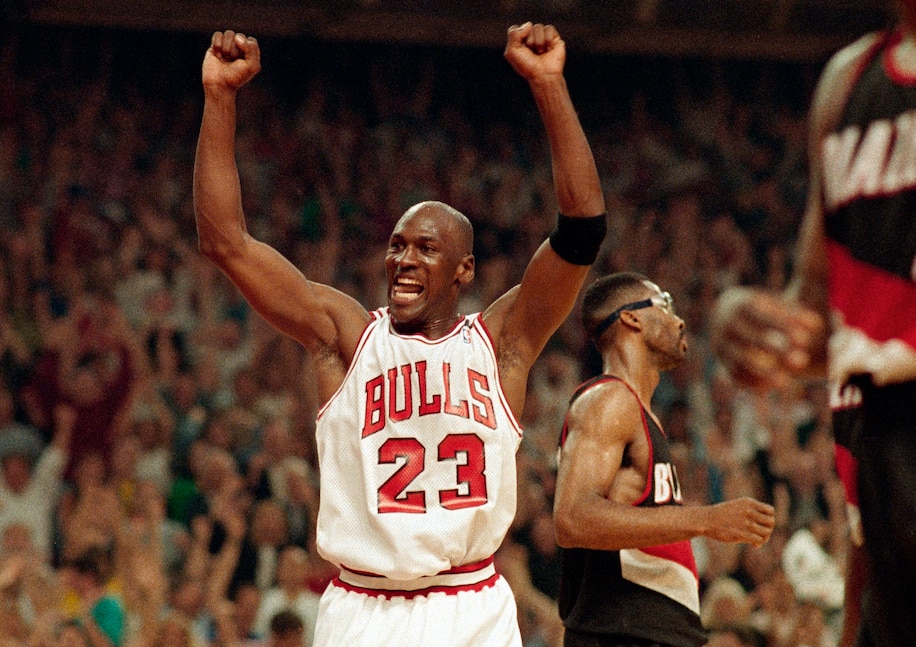

“The Last Dance” was a towering tribute to Michael Jordan’s otherworldliness. The titles, the talent, the impact he had far beyond basketball.

It also showed Jordan to be deeply human, as flawed and contradictory as the rest of us. He could be petty and cruel, and his commitment to decades-old grudges was as unsettling as it was entertaining. But he also could be caring and kind, devoted to the people and things that mattered to him.

“My passion on the basketball court should have been infectious, because that’s how I tried to play. I played for them,” Jordan said at the end of the documentary. “Started with hope. Started with hope.”

Playing before there was social media, Jordan was always a mythical figure. Oh, there were stories about how cut-throat he was, and he never tried to hide his disdain for Chicago Bulls general manager Jerry Krause. But that smile and his made-for-Madison-Avenue image convinced much of the world that he was as good a person as he was a basketball player. That if he lived in our neighborhood, we’d be fast friends who’d hang out together in the offseason.

But there are no saints, in sports or anywhere else.

Too often, we put athletes on pedestals, conferring personal traits upon them to match their physical skills. But we don’t know these people. Not really, anyway. The godlike status we granted Jordan did him a disservice because there’s no way he could possibly have lived up to it.

Some who watched “The Last Dance” were disillusioned by how spiteful Jordan could be, then and now, and were dismayed at the enjoyment he seemed to take from it. His own teammates called him a bully, and even some who had clearly earned Jordan’s respect were never more than acquaintances.

Others criticized him as selfish, wondering where his then-wife and children were in the hagiography. He also refused to take political stands, not wanting to alienate any of the folks who bought his shoes – to say nothing of all those other products he hawked.

This isn’t to say Jordan lacked feelings or humanity. He had endless love and loyalty for those who did get close to him, as evidenced by his relationships with the men on his security team and his pronouncements that he would not play for anyone but Phil Jackson. His acts of charity were numerous, and often done out of the public eye.

Even the harsh treatment directed at his teammates came from a place of good, although misguided, intentions.

But Jordan’s goal was never to be Everyman. He wasn’t trying to win Humanitarian of the Year awards or the Nobel Peace Prize. He wanted to be the best basketball player he could be, the best basketball player there was.

If you expected more from him than that and have come away disappointed, that’s your failing, not his.

“When people see this they are going say, ‘Well he wasn’t really a nice guy. He may have been a tyrant.’ Well, that’s you. Because you never won anything,” Jordan said in Episode 7. “I wanted to win, but I wanted them to win to be a part of that as well.

“Look, I don’t have to do this. I am only doing it because it is who I am. That’s how I played the game. That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that way, don’t play that way.”

Jordan’s participation in “Last Dance” was essential, and it says something that he was as open as he was. Sure, there was some revisionist history. But Jordan did more than simply allow the filmmakers to explore the unflattering aspects of his character, he actively participated in it.

Maybe he wanted to explain himself or soften the harsh glare cast upon him. Or maybe he recognized what all of us came to see these last five weeks: As enthralling as Jordan was as a god, he is equally fascinating as a human being.

This article was republished with permission from the original author and 2015 Ronald Reagan Media Award recipient, Nancy Armour, and the original publisher, USA Today. Follow columnist Nancy Armour on Twitter @nrarmour.