By Bob Nightengale |

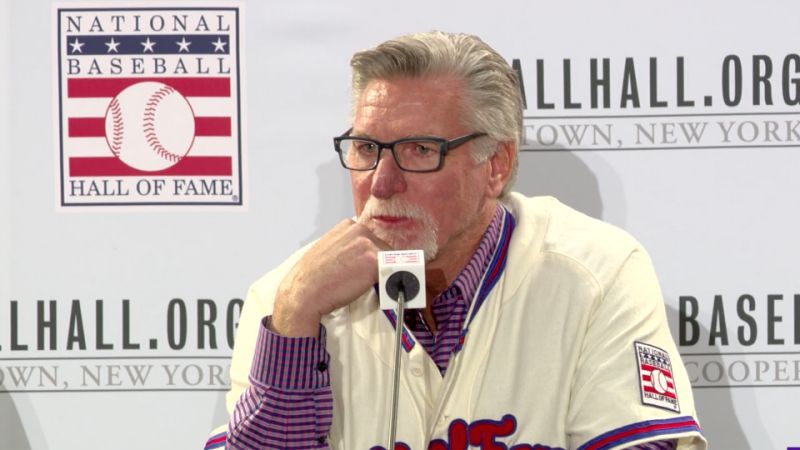

Can you imagine Jack Morris, who once broke blood vessels by slamming the ball down so hard in his manager’s hand, trying to keep his cool in today’s era when data points, and not performance, dictate how long you stay in a game?

How would Twitter react to Vladimir Guerrero, who never walked more than 84 times in a season? Would Alan Trammell be scorned for averaging only nine homers a year? Would Trevor Hoffman be belittled for his career 2.87 ERA? Would Chipper Jones be considered old school for never striking out 100 times in a season, or would Jim Thome be considered ahead of his time, once leading the league in strikeouts and walks, and still hitting 33 homers?

“All I can say is,’’ Morris said, “thank God I played in the era I did. Thank God!

“Can you imagine?’’

Uh, no.

This illustrious Hall of Fame class of 2018 — Jones, Thome, Guerrero, Hoffman and Today’s Game committee choices Morris and Trammell — played in a different era, a time when everyone knew who was leading the league in batting average, and not WAR. When players sat in clubhouses for hours after games talking baseball instead of scrambling home to play video games. When hit-and-runs, stolen bases, and advancing the runner actually occurred on a nightly basis. When 20-win and 100-RBI seasons were considered elite, and not a statistical anomaly.

This may be the last Hall of Fame class inducted into Cooperstown that played the vast majority of its career before analytics commandeered the sport.

“I mean, we’re not playing for spin rate,’’ Morris said. “We’re not playing for launch angle. And we’re not playing for exit velocity or, you know, ground efficiency.

“We’re playing to win. It’s W’s and L’s. I’ve been telling people for over a decade now, you know, all these numbers don’t matter. It’s letters that matter: W and L.’’

Morris admits one number that’s appreciated nicely over the years is a player’s paycheck.

“When I talked to guys from my era,’’ Morris said, “we’re all grateful that we played when we played. There’s obvious reasons why it would be advantageous to play in today’s game, and most of that revolves around money.

“But it’s funny, I think if I would have grown up in this era, I’d be just like the guys today. You know, the manager gets me and 5 2/3 [innings], well I’m done. That’s it. Go get them relief pitchers.’’

Yet, when asked if he would have kept his cool if he were pitching a shutout, and told he was coming out because he was about to face a lineup for the third time, Morris laughed.

“You know my reaction,’’ Morris said. “You don’t even have to ask that question. But here’s the thinking: those are the people that taught me how to do that. [Detroit Tigers manager] Sparky [Anderson] taught me how to do that. He was probably going, ‘Oh, God, I’ve created a monster.’’’

Yes, like the time Morris snapped when Anderson came to get him, with Anderson calling him into his office after the game and letting him know that will never happen again.

“Sparky had his little Sparkyisms that when he went out to get the ball from the pitcher he kind of clapped his hands twice, and put his hand out,’’ said Trammell, Morris’ former teammate. “Well Jack being the competitor that he was, he was so hot he didn’t want to come out of the game that he slammed the ball in Sparky’s hand and he broke some blood vessels.

“Often times, you know, Jack was very remorseful after the fact. But his hot blood, you know, it was real.’’

Hoffman, who grew up watching his older brother, Glenn Hoffman, play for the Boston Red Sox, went old-school the night he saved his 600th career game. He gave a quick speech to his Milwaukee Brewers’ teammates, retired to the trainer’s room, and sat there with staff members, clubhouse attendants and teammates for nearly six hours, telling stories, and downing a few beers.

It was vintage Hoffman, who realizes those days have gone the way of trains and flannel uniforms.

“It’s kind of dissipated,’’ Hoffman says, “because everything under the sun is in the clubhouses. I don’t know if it’s a video game thing, or if it’s just kind of social media type of stuff that you know can be [exposed] in the clubhouse.

“One of my greatest thrills was being able to hang out in a big league clubhouse. I appreciated being able to pick the brains of the people I was around, whether it was coaches or teammates to kind of hash out what just happened for the last three hours of the ballgame and try to get better at my craft. And you do that by communicating some of your thoughts and what you think through your lens and maybe bounce those ideas off and get a different perspective.

“And so I definitely think it’s beneficial. I’d love to see some of that come back more.’’

Those days are gone, and aren’t coming back, just like the time Morris pitched a 10-inning shutout in Game 7 of the 1991 World Series, finishing the year with 283 innings. Or the years when Guerrero came so close to actually having more home runs than walks. Or the 1,918 games that Trammell and Tigers second baseman Lou Whitaker played together, the most by a double-play duo in baseball history.

Morris pitched 175 complete games, with 175 former pitchers actually having more in their career, but his plateau may never be reached. There’s no active pitcher with more than 38 complete games, with 45-year-old Bartolo Colon and 37-year-old CC Sabathia nearing retirement, and no one has more than two complete games this year. Considering pitchers averaged a major-league low 5.5 innings per start last season, can anyone ever again reach 100 complete games again, let alone 175?

“Probably not unless baseball finally takes a good, hard look at the way the game is played,’’ said Morris. “I would love to see the Commissioner install a rule that you can only have a maximum of 12 pitchers on the roster. That would force managers to let the starters go deeper, and that might help cultivate more complete games.

“But it’s not going to happen unless something else changes, and the way it’s played today, it looks like that might be even further and further away from happening.’’

The game today is filled with players who may be more talented than their predecessors, with as many as 10 who likely would be Hall of Famers if they stopped playing tomorrow, but it’s a different game this Hall of Fame class grew up playing.

It doesn’t make it wrong, or necessarily worse depending on your generation, just different.

“I’m really glad,’’ Thome said, “I played in the era I did. I feel blessed I was in that old-school era of that time of the game.’’

Said Trammell: “I enjoyed those days, I’m not going to lie to you. I’ll cherish those for the rest of my life.’’

It’s an era that will be proudly celebrated Sunday, and hopefully, will never be forgotten.

This article was republished with permission from the original publisher, USA Today. Follow Bob Nightengale on Twitter and Facebook.