By Bob Nightengale |

They’re the ones nobody ever sees.

They’re not introduced in the opening-day pageantry. They don’t wear uniforms. They don’t have lockers in the clubhouse.

Some even have weird titles, just to protect their anonymity.

Yet, behind the scenes, there are proving as invaluable as any staff member in a Major League Baseball organization.

Mental skills coaches, employed by a record 27 baseball clubs to open the 2018 season, are valued more than ever.

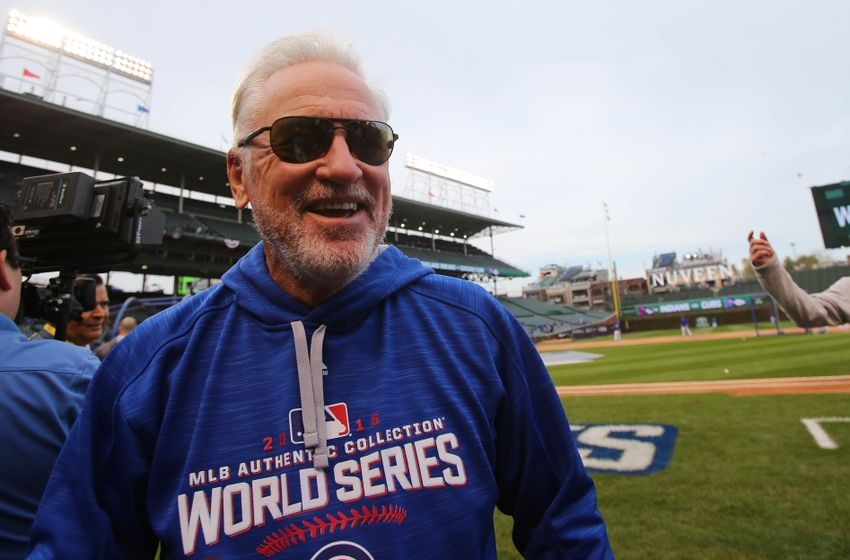

“If you said mental skills before,’’ Chicago Cubs manager Joe Maddon says, “that was an absolute sign that you were weak among the old-school guys. Deep down, there were a lot of guys who wanted to talk to them, but they knew that if they were seen talking to them, it would be seen sign as a sign of weakness. And the manager might think less of him.

“That was an absolute fact, and even today, I don’t think that stigma has been totally erased. To think that psychology is an indicator of weakness, truly is an ignorant statement. When people are fighting it, it’s only because they don’t understand it.

“It’s no different than your hitting coach, your pitching coach, your infield coach. A mental skills coach is going to help you think better, think more clearly in the moment, and control your emotions.’’

In the words of the late Yogi Berra: “Baseball is 90 percent mental. The other half is physical.’’

Seven years ago, there were 20 mental skills coaches who were being used by major-league clubs. There now are 44 who are either full-time employees or are consultants to teams and members of the Professional Baseball Performance Psychology Group.

You think Los Angeles Dodgers All-Star closer Kenley Jansen will be left alone after giving up a game-losing homer in his season debut, and blowing a three-run lead for another Dodgers loss in his encore?

Only the San Diego Padres, Atlanta Braves and Kansas City Royals do not feature some form of a mental performance department.

“We spend so much time on physical instruction,’’ says Andrew Friedman, Dodgers president of baseball operations, “that it just makes sense to have resources on the mental side as well. It helps guys because things are so more visible, and dissected in so much more detail, there’s more pressure.’’

Says New York Yankees GM Brian Cashman “Our job is to put our players in the best position to find success, and that means not just physically, but mentally and emotionally at the same time. We’re trying to exercise all of the muscles, including the brain.

“I remember when I first approached George Steinbrenner years ago, and I hired Chad Bohling I said, “The Yankees should be using every tool in the tool box, and this is one tool we don’t have. George said, “Go for it!’’

Bohling, whose title originally was director of optimal performance, is now beginning his 14th season with the Yankees, and leads a staff of five mental skills coaches in the organization. Bohling was not directly involved in all the Yankees’ managerial interviews before hiring Aaron Boone, but also is utilized in their interviews with their potential top draft picks.

“He’s a vital resource,’’ Cashman said, “for our entire company.’’

Tewksbury, a former pitcher who won 110 games in his 13-year career, is baseball’s lone mental skills coach with a master’s degree in psychology who also played in the big leagues. He was an All-Star who finished third in 1992 Cy Young Award balloting, and was released twice. He was a 17-game winner, and a two-time 13-game loser.

He grew up in an era when players were afraid to be seen talking to a sports psychologist, and now has written a book detailing his work: “Ninety Percent Mental: An All-Star Player Turned Mental Skills Coach Reveals the Hidden Game of Baseball.’’

With clubhouse camaraderie not as vibrant as it once was – and players likelier to retreat to the relative solitude of electronics – human connection remains important.

“There’s so much down times and this game is so result-based,’’ Tewksbury says, “and the combination of the two causes a lot of anxiety. Just to be able to have someone talk about it with can relieve some of that pressure.

“The demands of the player have become different. They’re at the clubhouse earlier, the games are longer, and when the game is over, they just shut down.’’

It may be a team sport, Ravizza says, but it’s really an individual sport within a team.

“Thing about it,’’ Ravizza says. “The pitcher stands alone on the rubber. The hitter stands alone in the box. You’re all alone.’’

Charles Maher, the Cleveland Indians’ sport and performance psychologist, says social media can complicate matters. Cubs All-Star third baseman Kris Bryant takes Twitter off his phone when the season starts. Boston Red Sox starter David Price now goes weeks without even looking at social media. And Tewksbury strongly suggests to everyone that they don’t dare look at the social media comments because of all of the negativity.

“Players need to be careful whatever they do because of social media,’’ Tewksbury says, “because they have the constant access with people that criticize them. If they choose to focus on the criticism, it doesn’t put you in a good place. You have to eliminate those distractions, get rid of that negativity.’’

Tewksbury also warns players to stop watching video during games. He hates seeing hitters race to the video room after virtually every at-bat, watching what they did wrong, or dissecting an umpire’s calls.

“It just reinforces the negative, and puts more pressure on yourself,’’ Tewksbury says. “The use of video should be used as a tool to review after performance, not during performance. You know what you did wrong. Why do you have to reinforce that?’’

Now, it’s more important than ever early in the season, mental skills coaches say, to avoid the distractions. It’s rough when an All-Star first baseman like Paul Goldschmidt of the Arizona Diamondbacks sees his .083 batting average on the huge Jumbotron. Aces like Carlos Martinez of the St. Louis Cardinals see that bloated 8.31 ERA in the boxscore. Championship-caliber teams like the Cubs open the season losing three of their first five games to the likes of the Miami Marlins and Cincinnati Reds.

“You don’t want to let a poor start distract you and take you out of the routine you developed,’’ says Maher, who originally began working with the Chicago White Sox in 1988. “You don’t want to let the first few games of the season influence you to make adjustments just four games into the season. You have to keep your focus, and that’s where the mental skills play a big part.’’

Those days are long gone when former Angels manager Gene Mauch used to tell Ravizza he didn’t want him around, permitting him to talk to only pitchers because of his friendship with pitching coach Marcel Lachemann. Mental skill coaches are not only accepted, but embraced, with managers such as Dave Roberts leaning on Eric Potterat, Dodgers director of specialized performance programs.

“He kind of taps into me, making sure I’m thinking the right thoughts,’’ Roberts says. “I use him to bounce ideas off during the year. It’s just a great resource.’’

Who knows, when the outlook looks dire, those developed mental skills can be just the thing that can turn a crushing Game 7 defeat into a World Series championship.

Just ask the Cubs, who established their mental skills program before the 2015 season still credit right fielder Jason Heyward’s speech during the rain delay in Game 7 against Cleveland to help end their 108-year championship drought.

“That was one of the most impressive things I’ve seen with Jason Heyward showing the mental toughness in that rain delay to be able to step forward,’’ says Ravizza, whose relationship with Maddon extends to the 1980s. “Here he was struggling all year, but at the same time, he showed he had the ability to lead.

“That will never be forgotten.”