By Cheryl McCormick, M.S.S. |

When it comes to a performance pyramid, soldiers must learn, train, and perform like elite athletes. These tactical athletes must continuously adapt, learn, and exert focus within a winning culture. Furthermore, tactical athletes must have a burning desire to compete within their job and to fight with pride for their country. Soldiers, like athletes, want to win and winning is what makes us proud!

Often, those with little understanding of how military members train do not recognize the similarities between these two professions.

Common traits between traditional athletes and tactical athletes: competitiveness, leadership, self-confidence, self-discipline, and positive mindset. Similarities between athletes and soldiers stem much further than the actual playing field. It is safe to say that like athletes, soldiers must employ empathy, learn various aspects of psychological training that can keep individuals focused under intense pressure to perform, and be physically healthy and fit to perform duties.

A unique kind of tactical athlete is a Special Operator. Special Operators are the 80% solution to multiple job disciplines. These individuals rarely specialize in one job. These individuals must train in each environment in which they must wear multiple hats to fulfill their profession. Unlike conventional forces, Special Operators deploy a smaller force. Although there are Special Operators in Special Forces, there are also other professionals that assist in other types of work. These professionals, however, are specialized within their jobs.

It is often believed that a Special Forces person specializes within a specific skill and are the best within that skill. However, enablers are the specialists within a job. Enablers are individuals like intel, explosive ordinates, and medical personnel that are attached to teams. These professionals go through many years of training to become specialized, and then become attached to special forces teams with Special Operators. To clarify more specifically, doctors, psychologists, dog handlers, performance trainers, and others can be in special forces, however their training is much different than those who are the Special Operators. It is important to identify that although these professionals make up Special Forces, the training is different.

Special forces span throughout all branches of military services. Some of the most known are Navy Seals, Green Berets, Marine Raiders (MARSOC), and Air Force Special Operations. Special Operators are not “specialists” in the traditional sense of having a single specialty.

Altogether, this presents you with the complexities in which everyone must fulfill during a deployment. It is important to note that the job of a military service member is the deployment, and the workups are the training for the deployments. Like an athlete’s job is to compete, and their camps are for training for their competitions.

Working within the sport industry for many years as a sports research scientist and focusing heavily upon athletes’ performance in both mental and physical aspects of training, I have had a long-time desire to discuss the similarities between military and sports figures. While being married to a Special Operator for nearly 13 years, out of respect for the nature and security of his former position, I wanted to wait to conduct an interview for others to read. However, being recently detached from the military, provided me with a great opportunity to interview my husband, Christopher McCormick, a Marine Raider, Special Operator with MARSOC, and former Recon Marine who as of recent, was in the Marine Corps for almost 17 years.

In this interview, Mr. McCormick provides insight among several topics relatable to the sport industry. My goal for my readers is to take away as much insight among topics relating to mental mindset, various stressors, adaptability, training regimens, decompression phases, transitioning outside of the military, and more! To review the full length of this article, please navigate to the website link provided at the bottom of this article, and search for “interviews.”

Interview: SSgt. Christopher McCormick

What are the top 3 qualifications or experiences you have had in the military?

Like many athletes, I grew up in a rough setting, between two flea markets, a railroad track, and a trailer park, so any experiences outside of that were exciting. The first thing you hear about in the Marine Corps is Marine Scout Sniper. It is what most guys want to do. Because I wanted it so bad, I did it. This school was the most mentally and physically exhausting school that I have ever been to, to this day. The next two were free-fall school and dive school. Your very first jump in free fall, they throw you out of the plane, by yourself. I’d advise you to get training before you do this. My third one would be dive school. Dive school was in Florida. It was a beautiful and awesome experience. During this school (3 months) our final excursion was to perform a 15-mile fin in the intercoastal. And for my last was SERE (survival evasion resistance escape) school. During this course, they dropped me off in Maine during the middle of winter. They gave me a map and a compass with a direction to walk before you get captured. Walking up and down the mountains of Maine was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. The scenery helped me stay mentally focused and sane to finish the training.

Did you have any idea of how long you would stay in the military?

When I first joined, I had little known of how long I would stay in. Obviously, I had to fulfill my 4-year contract, but it was unclear to me at that time. However, it was within my first year as a Recon Marine, that I began developing relationships and cohesion with my fellow Recon brothers, and eventually got married and decided this job had become my career. It was during that time that I began setting goals for myself, and my first goal was to become a Scout Sniper.

Did you play sports growing up? If so, did you compete in them the same way you did in the military and why?

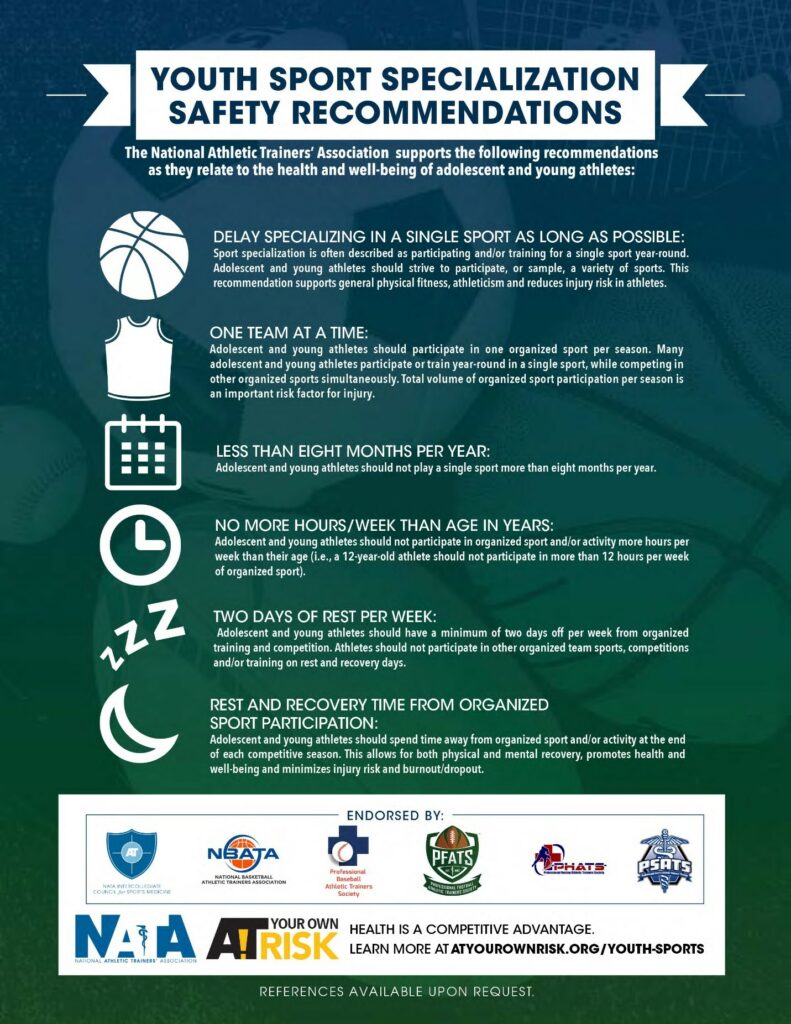

Yes. I played soccer as a youth athlete and wrestled throughout high school. However, I had little time to engage in sports since I had to hold down a job if I wanted any type of spending money. As far as how I competed, I competed harder during my military career than I did in my sports. The reason for this was partly because the military was my job, it was something that challenged me in a different way than any of my youth sports did, possibly because I had little time to truly focus on the sport itself, due to having to fulfill other needs and obligations. Additionally, I was challenging myself like a college athlete, because if I stayed in the same place and did not work hard on my physical and mental strength and capabilities, I could lose my position as a Recon Marine. This is due to a perform on call standard that must be met at any time. Perform on call means that anytime they call on you, you must be able to do it. Imagine it like an NFL player who has no off-season and must compete year-round. They would be prone to a lot more mental and physical injuries.

Did you ever feel like you were competitive with others (while trying out for jobs or during deployments)?

You are always in competition with your peers. Everyone wants to be the best. This is how you get specific positions or as in sports, get drafted to the best teams. I was one of the highest shooters from the Special Forces course and it landed me into the commando team which is a very aggressive and kinetic combat team. If you are going through an assessment and selection process, the competitiveness is increased because there are only so many slots available. They will only take the best. Therefore, competitiveness is something that most individuals become.

When did you experience your first mentally challenging task in the military, and how did you push through it?

The first day of boot camp, I sprained my ankle. It was such an intimidating environment due to the drill instructors yelling at me, however I would just push through the pain. Think of it like having blisters on your feet as a runner, instead of walking off the course, you push through the blisters breaking open and causing your gate cycle to change. I had to remain quiet and find a way to get through the day in pain if I had wanted to get through boot camp. I also never wanted to stand out to the drill instructors because I would become a target for them throughout boot camp.

When you became a Recon Marine, did you endure a lot of mental challenges or did the job become easier over time, so you didn’t recognize the mental stressors of the job?

My job did not get harder until I got into special forces. Let me emphasize, Recon is not part of Special Operations Command, however if Special Forces had a need for a Marine element or team, they would call up Recon. While in Recon, I was young and was being mental and physically built up, by going to jump school and dive school, and deployments. As I continued going through these courses and experiences, I became mentally and physically stronger. However, overtime there was wear and tear, but remember, we had no off-season.

As a Special Operator (MARSOC), what were some of the most difficult mental and physical challenges that you endured?

As a Recon marine for about 6-7 years, I decided to go into MARSOC (as a special forces operator also known as a critical skills operator). The differences between these two was Recon was shoot, move, communicate. Think of it like a Lineman, where the goal was to know the entire football field and tackle the quarterback. MARSOC however, was like the quarterback, the spokesperson, the face of the team, where if you fail, everyone is quick to point fingers at you. When I got to Special Operations, the battlefield was more complex. It was like going from college to a professional team. For MARSOC, we didn’t just take out the bad guys, we had to also do the village stability platform, more economic and political work. In this, the biggest challenges were when I had to go do combat operations and take out the bad guys and then the next day, I would put on a suit and walk into an Embassy and brief people from Harvard who had MBA’s, while having to calm my nerves from the day’s prior work. Here’s some insight: For a week, you plan an operation, you study your enemy, you must play his game book as you watch him, and then you must build your plan. You get a thumbs up from the commander and you get your team of 4 Americans and 30 Afghan commandos ready to go. At this time, you get your entire team ready to go, jump into a helicopter with your team at 1am. An hour or two later, you land on the enemy’s house, and you get into that gun fight and hope that your plan works. After going through the gun fight, losing some of your team guys, and enduring what most people could not imagine, you go through the final steps and collect your wounded shoulders, fly back to a hospital, covered in blood, and try to save your teammates lives. After this is all done, you have to speak to high level generals while collecting yourself, you must present yourself as someone calm, and collective. If you do not look stable, mentally, they can question your decision-making abilities. I would say the mental pressures from this type of work do challenge some to the point of no return. And mind you, you must return home, from enduring this throughout a 6–9-month deployment, all while being mentally sane.

Would you provide insight into how you gained adaptability in your work during trying times (deployments and missions)?

This is hard to just say. I believe that bootcamp was the platform that helped build me up to endure trying times, throughout my military career, regardless of what job I performed. As far as being a Recon Marine and Special my adaptability came from being humble, and watching guys retire. I was always a hard head, I wanted to run faster, jump higher, etc. However, listening to the older guys who had a long-time experience in what I did, those are the guys who truly helped my adaptability process.

How difficult were your training regimens as a Special Operator (workups)?

Being in Special Operations, you are now part of being in a special sport. You are training to be the best of the best. You don’t stay in a camp and do little, you go to them and receive the best of the training. Being away from your life at home, your family, your children, and spouse, is extremely difficult. We don’t train to standard; we train to time. This means that if you want a sprinter to run 100-meters and hit their goal time, it would be performed during their training process, and then they would be done for the day, until their next training event. However, for individuals like myself in my job as a Special Operator, I would have to continuously hit that goal, rain or shine, sleep or no sleep, financial problems, whatever you had going on in your life, with sometimes little or no off-time. It was like operating on call. So, to answer the question, training was extremely difficult, throughout my entire profession. It appears to be easier at times, however, it gets more intense and aggressive, so I could never really say that I was ever relaxed.

Would you provide insight on your decompression phases (coming home from a long school for training, finishing out a deployment)?

Another hard one to answer. Unfortunately for my wife and children, I never decompressed. When I would come home, I would jump on my motorcycle and ride as fast as I could to get that thrill. Part of my decompression would be during times from coming back from deployments. SoCom would rent out hotels in a town (around the U.S.) and we would come back and have three nice meals per day, cocktails, psychologists, basically pampering me back to normal health. We would do this for about 3-5 days, to get back to our families, and lifestyle. One of the most challenging aspects to coming home from deployments, would be my decompression phase (3-5 days), and then being home for give or take 1 month, and then turning around to leave again to start training for another.

What advice would you provide (mental and physical performance) to new candidates that want to pursue a job within MARSOC as a Special Operator?

Take off-time. Take time to make sure you are good, for you. Take time to go to therapy. Take the time to take care of your body and mind. Talk to the psychologists provided to you. Don’t let what you hear about losing your job if you seek psychiatric help. Take care of yourself. My biggest advice is to not look at it as a short-term investment. Look at your job as a long-term investment, therefore, you need to take care of yourself first and make sure you have the mental and physical capabilities to provide for many years.

After serving almost 17 years in the military, what are some of your most important take-aways from the jobs in which you performed?

The first one, is to have built the relationship with my wife and kids. I always threw the military in front of them instead of focusing it where I should have with them, being my number one support system. My second would have more diverse training. I focused so much on my military training versus focusing on my education and what could have helped me transition out of the military with a stable job. However, I want to say, that only for a short time in your life, can you become a professional athlete or a Special Operator, whereas you can always go back to school, no matter what your age is. I only say I wish I would have received my education in the military to have helped with the transition into another job once getting out.

What is some advice that you would provide people (mental and physical) who are interested in your line of work, psychologists who study and work with guys like yourself in the military, and for people who have little knowledge about the military?

This is a loaded question. First, with psychologists, you need to befriend them. You need to go out on a weekend, grab a drink and really try to teach them about who you are as a person first, second as a Special Operator. If, as a psychologist, you want to analyze one of the guys, you must be one of the guys. Trust is huge. If you don’t have trust with a guy like me, then you will get nowhere with them, especially if the guy doesn’t want to open up. You’re talking to guys who have worked in intelligence for 20 years. You have no idea what that guy has gone through. The human-to-human relationship is the most important key. Empathy is not gained from a schoolbook. It is gained through experience. As for people who are interested in my former line of work, I would tell you that it’s all about the foundation. You can go into this kind of work; you can build a mansion on sand, and it won’t last. You must start this process from a young age. You must practice self-discipline to help you strengthen yourself into this line of work. Sports, helps me develop a foundation and structure that built me up. The competition helped me understand that I could endure the challenges and the pain. When you walk out of your house with that beanie on in freezing temperatures, it’s game on! You must know how to endure that pain and run with it!

Cheryl McCormick, M.S.S. the owner and founder of Gravitational Performance and School of Sports Science and is also a doctoral student at the United States Sports Academy. Her former years as an athlete has guided her interests into education in sports and passion for research as a sports scientist, content developer, educator, and director of coaching education- working in sports medicine, sports nutrition, and sports psychology. Currently, Cheryl is a board member of the NC State Advisory for the NSCA. She can be reached at gravitationalperformance@gmail.com.